Why do you need a bushcraft knife?

Bushcraft is, in short, making the most of nature with the bare minimum of equipment, but not as rudimentary as survival of course. That explains why a bushcraft knife often is a bit lighter and thinner, as it shouldn’t see the abuse a survival knife could get. So where you’d definitely want to be able to do some batoning (cleaving wood by striking the spline of your knife while driving it through), with a survival knife, you normally will take a small axe for that in bushcraft. That way you can take a nimbler bushcraft knife that’s easier to work with and will often perform better than a thick, large blade. Having said that, most bushcraft knives will surely withstand sensible batoning successfully, but will draw the line when you go full-out caveman on them.

A thinner blade offers advantages that will make sense in bushcraft. It will cut lighter and more intricate. It’s easier to do some detailing with them. As a bushcraft knife will primarily be used to make wood into useful things, it’s important the controllability is good. Think in line of things like making a shelter from branches, cut notches or slots, sharpening sticks and make kindling to start a fire. A bushcraft knife is also often used to prepare food and for this reason many of them feature a nice flat edge that makes it easy to cut up meat and chop herbs and vegetables.

Which metal? The number one campfire discussion!

Simply said, you can choose between stainless steel and carbon steel, regarding to the blade of a bushcraft knife and both have their fair share of advocates and opponents, which’ll surely make for a nice (and endless) campfire discussion. Stainless steel has the advantage of not being too sensitive for corrosion, making it perfect for salty or extreme wet conditions. However, stainless steel is a bit softer than carbon steel, making it less tough. That’s why it won’t hold its edge as long and as it’ll sooner bend than ‘crumble’, sharpening will take longer.

Carbon steel is known for its incredible toughness and the ability to hold its edge for quite some time. Because it’s very hard, it’s quick and easy to sharpen. Corrosion will ruin the edge of a blade faster than normal use will do, but you need to be at sea for corrosion to really play havoc with your carbon steel blade bushcraft knife. In any other circumstances, regular use and cleaning will keep your bushcraft knife free from corrosion. Just don’t cut a lemon without cleaning the blade afterwards or put a wet knife in its sheath and leave it there for weeks. One piece of advice: use food-safe oil to preserve your carbon steel blade when you’ll be preparing food with it.

Drop-point, clip-point and a tang

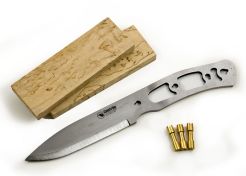

Often bushcraft knives feature either a drop-point or clip-point or something closely resembling those. The former being more robust and capable for some rough work, while the latter will let you work more detailed and refined when cutting and even drilling wood. And then there’s the part of the blade that’ll disappear into the handle. It’s called the tang and for those of you who will actually want to do some batoning, you’ll prefer a full tang, where the tang will go the full length and width of the handle. Often, the handle will then consist of two scales or it’s forged around it. Other options are a skeleton full tang (which will save you some weight), a pin shaped tang in different grades of taper or inversed taper or a tang that’ll only go partially into the handle, again in different shapes and sizes. Of course, a full tang will take the most abuse, but when you’re not using your bushcraft knife like an axe or machete, even a well-designed half tang can be extremely durable.

Prevent blisters?

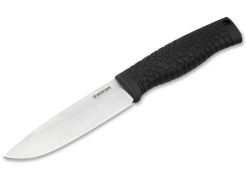

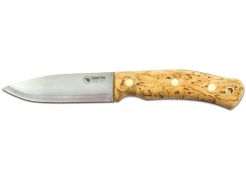

A bushcraft knife will be used often and sometimes for a prolonged amount of time, so make sure the handle lays comfortable in your hand and offers a good grip. Choose a handle without sharp edges and if the handle consists of two scales, make sure the rivets or screws are flat, but surely don’t stick out to prevent blisters. An often used material is still the good old wood. Wood offers a good grip under virtually every circumstance and feels warm and comfortable to the touch. Besides that, it’s chemically resistant, which isn’t always the case with plastic and rubber handles. The disadvantage of wood is that humidity and heat can make it to work or even crack, but with normal use and normal drying, you should be fine. Maintenance with a bit of oil from time to time is a good idea.

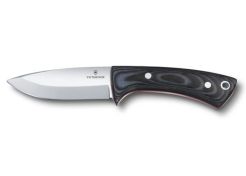

A bushcraft knife with synthetic handle is maintenance free and very easy to clean, while moulds won’t get a hold on it. By texturing the surface or use rubber inlays, they can provide a good grip. The range of available materials is immense, but as we don’t expect someone would want inlays of mother of pearl or is considering a metal handle that would freeze to your fingers when used in the cold, we just mention two popular materials: micarta is a laminate, made from layers of woven natural fibres, saturated with synthetic resin and compressed under high pressure. It offers a very good grip, is extremely durable and feels comfortable. A variant from this is G10, where the natural fibres are replaced with woven glass fibres.

Fast & secure delivery

Fast & secure delivery Secure shopping & payment

Secure shopping & payment Lots of expertise

Lots of expertise